Artefact of the month

In addition to interviews, documents and photographs, the CDZWiP archive also receives numerous objects of everyday use that ‘accompanied’ people in their wartime wanderings and now have a very high historical value and are a treasure trove of knowledge about the past. Each month, we present a selected artefact and give an overview of its history.

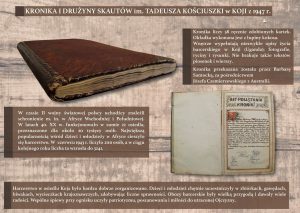

Chronicle of the 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Scout Troop in Koji (Uganda)

During the Second World War, Polish scouting was active in the Black Continent. The chronicle of the 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Scout Troop in Koji (Uganda) was donated to the Centre’s collection by Barbara Santocka through Józef A. Czemierzewski from Australia. You can hear more about scouting in Koji in an excerpt from an interview with Jozef Czemierzewski: Józef Czemierzewski, Koja – YouTube

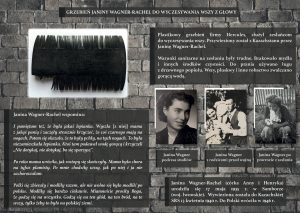

Comb of Mrs Janina Wagner-Rachel

Between 1940 and 1941, the Soviet authorities carried out four mass deportations of Poles deep into the USSR. The deportees lived in very difficult conditions. In the collection of the CDZWiP there are many objects of everyday use that were brought back from exile. We present the comb of Mrs Janina Wagner-Rachel. It was used to comb lice from the head. The interview with Mrs Wagner-Rachel was recorded in Krakow, Poland, in 2015 and is in our collection.

Pre-war Leica camera

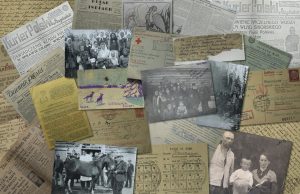

Pre-war camera by Leica (1930s) and 260 negatives of pre-war photographs and photographs from a stay in exile.

DURATION OF THE PHOTOGRAPHY: 1940s.

PLACE OF COLLECTION: Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic

DONATION: Janina Wagner-Rachel

The camera was taken into exile by Karol Wituszynski, owner of a photography workshop. The photographs mainly show everyday life in the Kazakh SSR. The negatives were developed by the Centre’s staff and are held in the CDZWiP Archive.

Picture of Our Lady of Kozelske Victorious

Donation by Mr Mieczysław Malinowski. It is 1940, the year of the Kozelsk II camp. For the prisoners of war, religious life plays a very important role, so they decide to create their own image of Our Lady of Kozielsk, which will refer to two miraculous borderland images: Our Lady of the Dawn Gate and Our Lady of Żyrowice. The prisoners are using a linden plank found during the clean-up, torn out of the iconostasis destroyed by the Russians. Until now, the plank has served as a cover for a herring barrel. The image of the Madonna is soon designed by Mikołaj Arciszewski, an atheist, communist and sole possessor of coloured pencils. The board is divided into two parts. One becomes a bas-relief by Tadeusz Adam Zieliński (MB Kozielska Zwycięska), and the other an oil painting by Michał Siemiradzki (MB Kozielska Różańcowa). Chaplain Nikodem Dubrówka consecrates both works of art on Holy Saturday, 12 April 1941. After the Sikorski-Majski Agreement was signed, the images are separated. The oil painting reaches Jerusalem, from where it arrives in Poland via Great Britain and Italy in 1988. The bas-relief becomes the knightly image of the Polish Army in the East. Together with the Polish soldiers, it travelled the entire combat route – through Persia and Palestine, all the way to Italy, where, after the Battle of Monte Cassino, it took on a new name – Our Lady of Koziels’ Victory. It then made its way to London with the Second Polish Corps. It is now housed in the church of St Andrew Bobola in the Hammersmith district. Our Lady of Koziel Victorious became the patroness of those rescued from Soviet misery, and after the war she accompanied Polish emigration.In our Centre we have a copy of the image of Our Lady of Koziel Victorious, donated by Mr Mieczysław Malinowski. Mr Mieczysław Malinowski had been travelling to the Borderlands since the 1990s, getting involved in rebuilding the Church in Volhynia. Together with Father Leon Krejcza (1912-1997; pre-war priest of Lutsk Cathedral; employee of the Metropolitan Curia in Krakow), he collected donations and passed them on to the parishes being rebuilt there. As a token of gratitude for his fruitful cooperation, Mr Mieczysław received from Fr Leon Krejcza a copy of the image of Our Lady of Kozielsk the Victorious, which he later donated to the Archives of the CDZWiP.

Suitcase made in Koji

A suitcase made in a leather workshop in a Polish refugee settlement in Koji (Uganda) in the 1940s. It is a gift from brothers Artur and Ryszard Woźniakowski. The Woźniakowski family were deported deep into the USSR on 10 February 1940. Artur and Ryszard’s parents worked in a copper mine and they attended kindergarten. After the Soviets announced the so-called amnesty in 1941, the Woźniakowski family reached Uzbekistan. There, the father joined the army, while the mother and sons made their way via Persia and India to the settlement of Polish refugees in Koji on Lake Victoria. It was inhabited by around 3,000 people. Among them were Artur, Ryszard and Jadwiga Woźniakowski. A hospital, a church, a cinema, a shop, as well as a kindergarten, primary schools, a general secondary school and a vocational school were very quickly organised in the settlement. Thanks to her experience at the pedagogical seminary before the war, Jadwiga worked as a teacher. The boys’ time passed on learning and playing. In spite of the difficulties of organisation and supply, in the settlement, in addition to administrative and cultural facilities, there were still factories – shoemakers, tailors and leatherworkers. Polish women not only sewed costumes for the theatre, but also made suitcases from leather, which Koji residents took with them when leaving Africa after the end of the Second World War. In 1948, after eight years of wandering, Artur and Ryszard Woźniakowski, together with their mother Jadwiga, packed their belongings into the suitcase presented here, heading for Poland.

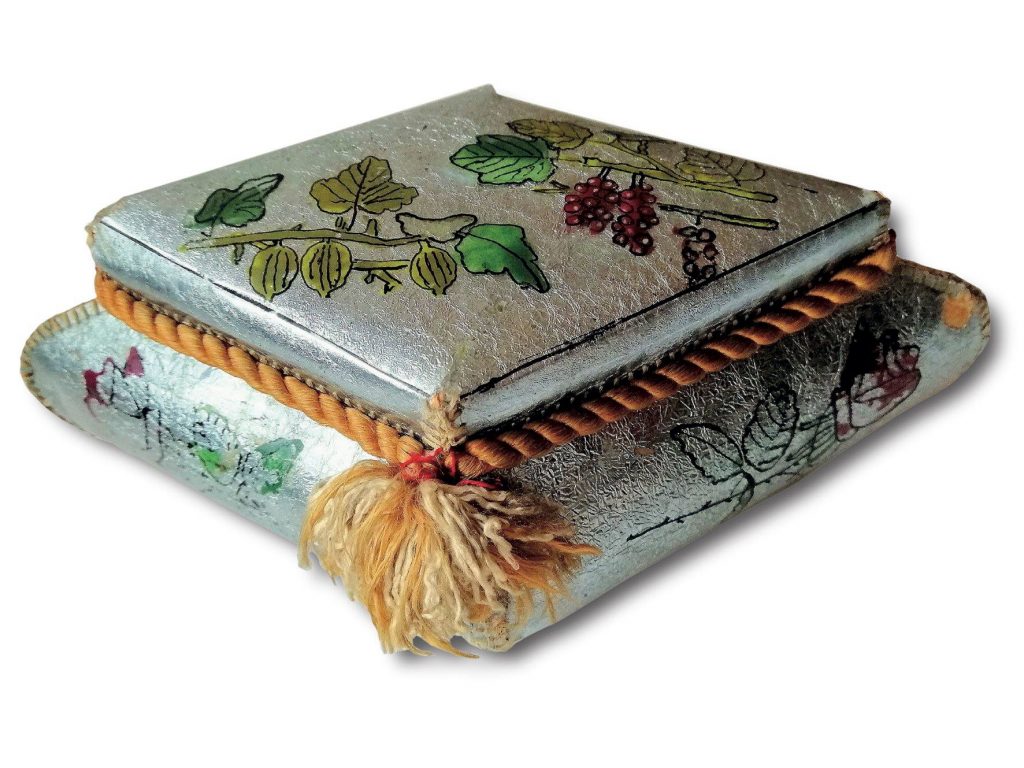

Casket of X-ray film

A casket of X-ray film made by a patient of the Tashkent Psychiatric Hospital. “After completing my summer internship, I was referred to the Republican Psychiatric Hospital [in Tashkent] for a psychiatry internship. […] Only a few days had elapsed when I was summoned to the hospital’s personnel officer to sign a contract of employment as a medicynskaya siestra (nurse). […] I eagerly took up my first duty. I was to work from the evening, from 7pm, until 7am. […] During the night, it was necessary to be constantly vigilant, perceptive, attentive and anticipatory, reacting quickly in the event of a rage attack in a sick person to ensure the safety of the children and myself. Constant intensity of attention, anxiety and even fear of possible excesses prevailed throughout the night. At every knock or the slightest rustle, one would run to that side to check the cause of the disturbance of the silence. […] Physically it was not too hard a job, but it was extremely strenuous mentally. It was very sad to see the children’s faces painted with suffering, indifference or trepidation.” This is how Stanislawa Chobian – Cheron, deported from Vilnius to Kazakhstan in 1952, recalls her work in a psychiatric hospital in Tashkent (Uzbek SSR). In gratitude for her care, the Polish woman received the presented casket from one of her patients. The box is in the shape of a rhombus and was made from X-ray film during therapy classes held at the hospital. The lid and sides were decorated with a floral motif. The artefact found its way into the Centre’s archives in 2011. Stanisława Chobian – Cheron – an extraordinary, determined woman, who in her life repeatedly undertook a silent struggle, and whose trust in liberation and a better tomorrow allowed her to achieve her dreamed goal – to obtain a diploma and become a doctor. She was born on 7 June 1928 near Lida. During the Second World War, her family became involved with the Home Army, helping escaping Jews and organising secret education. In 1947, Stanisława began studying medicine at Vilnius University, and her widowed mother employed people looking for work to help on the farm, despite Soviet prohibitions. In 1952, her mother, Wiktoria Chobian, was arrested and sentenced to prison for “kulaks”, and the children, Stanisława and Jan, were deported on the night of 13/14 April 1952 to the Dymitrov kolkhoz in Kazakhstan. Jan worked in cotton cultivation, while the determined and stubborn Stanisława began to push for the opportunity to continue her studies. This is what happened. The Polish woman studied in Tashkent, while also working as a nurse at a local psychiatric hospital. After difficult decisions and risky actions, Stanisława graduated as a doctor in 1954. In the meantime, after many efforts, the siblings met their mother in Tashkent so that they could leave for communist Poland in 1955. In the 1970s, Stanisława and her husband took advantage of political asylum and moved permanently to France, retaining their Polish citizenship, however. More in the book Wandering poppies by Stanisława Chobian – Cheron, Warsaw 2007.

Miniature book

The presented “Miniature Booklet or a short collection of the most necessary prayers and songs” was published before the outbreak of the Second World War – in 1931 in Częstochowa. It “travelled” a very long way with its owners – from the USSR through Africa to Great Britain, to find itself back in Poland, or more precisely in Krakow – in our archives. Prayer books and other religious objects, such as crosses, pictures and holy figurines, were often taken by people being deported to the Soviet Union. They may not have been necessities, but they helped religious people survive the difficult time of deportation. In exile, manifestations of religiousness were usually severely punished. Despite the prohibitions, Poles tried to organise their religious life – they met for religious services, held funerals and baptisms, created altars, sang songs at work and celebrated Christmas and Easter, often in hiding, away from the barracks. Common prayers and other religious practices, not infrequently met with aggression from the camp authorities. Interestingly, in difficult times, when schooling was limited, children learned letters and how to read just from prayer books. The miniature booklet, like the rest of the collection, was donated to the CDZWiP archive by Zofia Piskorz – Somchjanc, through her cousin Wiesława Drozdowska. Thanks to them, we can trace the entire path she traveled. Zofia, together with her mother and brother, was deported to the USSR and then, after the so-called amnesty, reached East Africa via Iran. Her brother Władysław left shortly afterwards for the Aeronautical Technical School in Halton, UK, and Zofia and mother Celina stayed for several years in the Polish settlement of Tengeru in Tanganyika (now Tanzania). In 1948, as part of a family reunion campaign, they arrived in the UK. Mrs Zofia has donated many photographs and artefacts to the CDZWiP archive, including the prayer booklet on display. Mrs Hieronima Drożak tells more about prayer in exile. We invite you to watch the report: Hieronima Drożak. Modlitwa na zesłaniu. – YouTube

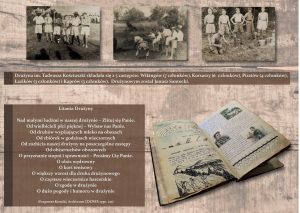

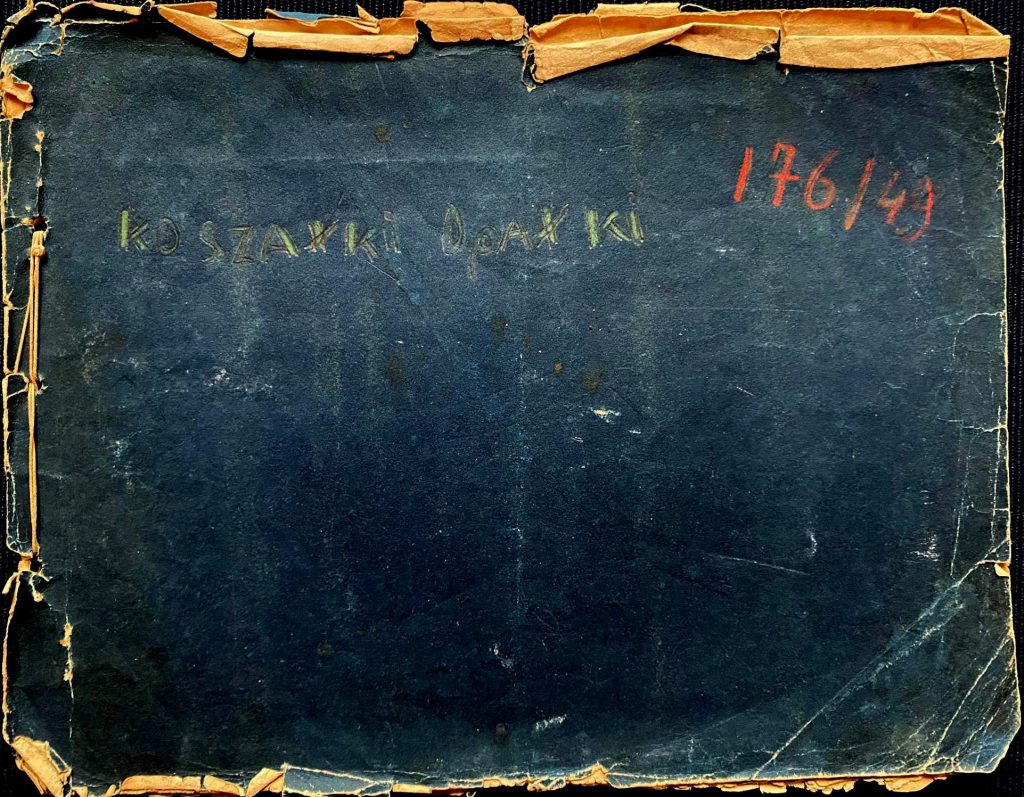

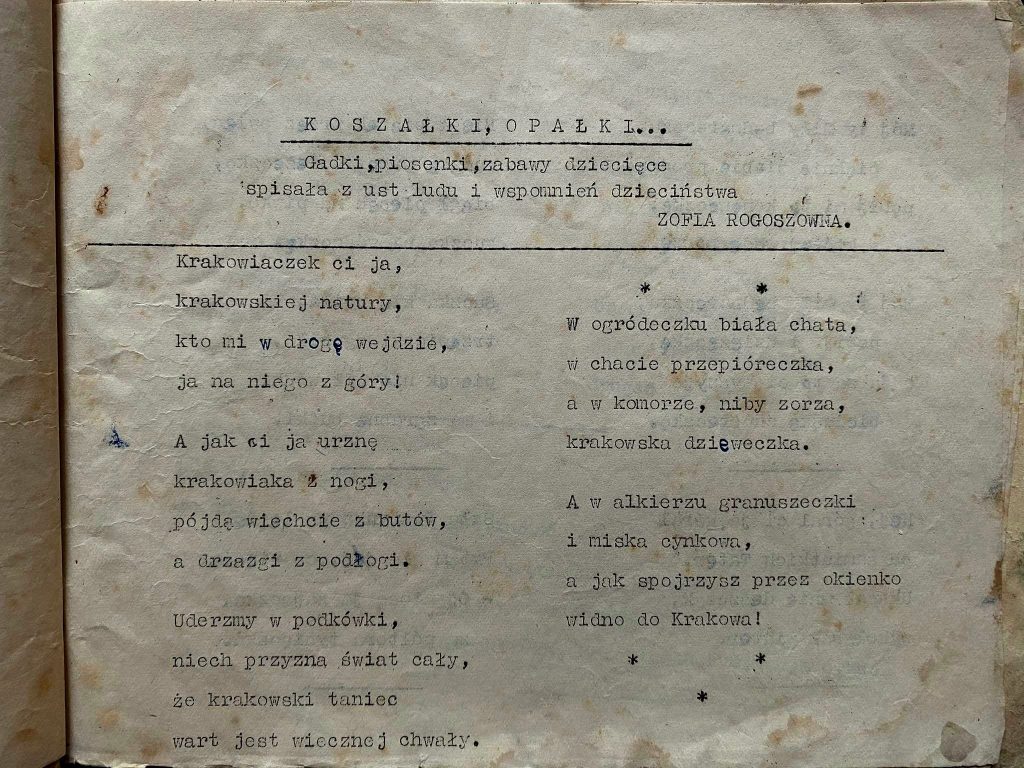

,,Koszałki, Opałki…”

“Koszałki, Opałki… Chatter, songs, children’s games written down from the mouths of the people and memories of childhood by Zofia Rogoszówna” (reprint). “Supplementary reading for the use of schools and day-care centres of the Polish Settlements in India. Reproduced through the efforts of the Delegation of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare in India, Bombay 1943.” The author of the collection “Koszałki, Opałki” is Zofia Rogoszówna, a Polish writer who was keen on collecting folk songs and using them in literature for the youngest. The booklet presented here is a reprint made in India in 1943 for children from Polish settlements. The original dates from the 1920s. “Koszałki, Opałki” brought back from India, was donated to the CDZWiP Archive by Mr Lech Trzaska, who also shared his story with us (2 times) – in 2011 and in 2020. As a child of several years, Lech Trzaska, together with his family, was deported to the USSR in the June 1940 deportation. After amnesty was declared in 1941 and he reached the south of the Soviet Union, Mr Lech’s father enrolled in the Polish army that was forming there. He died shortly afterwards. Lech was placed in an orphanage and travelled to Iran with other children. In Tehran he met up with his mother, who had escaped from the Soviet Union on another transport. They then reached India together and settled in the Valivade Polish Settlement. In 1948, they returned to Poland. In the Polish settlements in India, there were several primary and secondary schools, as well as vocational schools – mechanical, tailoring or household. There were day care centres, libraries, many theatre groups and interest groups, organised by teachers and tutors, who played a very important role in the lives of the children, often replacing parents and relatives lost too early. A major obstacle to schooling, was the unstructured curriculum. In the early days, everything was written on the blackboard or dictated. In the absence of textbooks and notebooks, children took notes on loose pieces of paper. The sheets of paper were then combined into scripts, which were often used by pupils in subsequent years. The level of teaching increased significantly when printed textbooks were obtained. Their publication in India was handled by Longmans Green of Mumbai, among others. The MWRiOP Delegation also purchased textbooks in the Middle East, mainly in Jerusalem and Beirut. New books were delivered to the settlements from time to time. Some were ordered from publishers in England and Scotland. Care was taken for the cultural development of the residents, ensuring that they had constant access to the library, newspapers and radio, and providing many entertainments in the form of social games, sightseeing trips or sports competitions.